Is Private Equity Right for You?: FAQs for Multi-Unit Operators Seeking Capital in 2011

You might not know it from reading the news, but there's a lot of money out there looking for a good home, and high-performing multi-unit franchise companies have become targets for private equity investors. Estimates of available private equity peg the pent-up funds at about $500 billion, more than enough pie for most multi-unit franchisees to get a slice--if they have what it take to appeal to investors.

Developments in the mergers and acquisition universe, along with the growth in large multi-unit organizations and a stabilizing economy in 2011, have combined to produce what experts predict will be a favorable environment for franchise sellers with the right stuff: a strong national brand; a positive cash flow for the trailing 12 months; an infrastructure able to leverage the investment; and an organization large enough to make the deal worthwhile in terms of the costs and time involved for both buyers and sellers during the due diligence/courtship process, which can take six months to a year or more. Real estate assets are a big plus as well. (For more on the 2011 M&A outlook, Click Here)

Even as the economy writhes its way toward recovery, however, getting your hands on the money--and your mind around the ramifications of taking on a private investor partner--is another story. Yes, interest in high-performing franchisee organizations by private equity firms is rising, but is this a good option for multi-unit operators in need of capital? Is the cost of money--an active partner, accountability, loss of autonomy to investors that typically seek a controlling interest--worth it to a franchise operator used to calling their own shots?

We asked a dozen players--franchisees, attorneys, and deal-makers of various stripes--to tell us what multi-unit franchisees should know about the current state of the private equity market, the pros and cons on taking on a private investor partner, and the tradeoffs involved. The answer, of course, is, "It depends." The financial terms of the deal are an obvious critical consideration, but more important, say many, is the relationship between the operator and the investment company. Is there an alignment of goals? Can an independent-minded operator get along with an active board during a partnership that can span five years or more?

How will a capital infusion help achieve a franchise company's goals over the short, medium, and long term? Is it needed for expansion within a territory or brand? Strategic acquisitions? An initial step toward an exit in 5 or 10 years? Or, for food and lodging brands, a way to pay for expensive remodeling obligations?

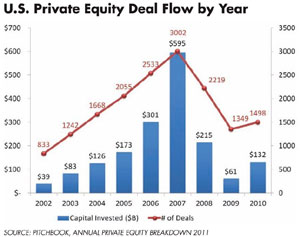

For most private equity players, the goal is to find a reasonably safe, high-return vehicle for investors to park their money in for a limited time and make a profitable exit. Following the end of the high-flying M&A years of 2005-2007 (see graph), many investors were disappointed by their returns in recent years, and are still fairly cautious about doling out funds--except to those with a positive cash flow and a track record of success backed by solid management practices. Balancing their investors' demands to find opportunities for their pent-up capital, private equity firms are climbing back on the bull in 2011, wary of waiting too long or seeing valuations rise.

For most private equity players, the goal is to find a reasonably safe, high-return vehicle for investors to park their money in for a limited time and make a profitable exit. Following the end of the high-flying M&A years of 2005-2007 (see graph), many investors were disappointed by their returns in recent years, and are still fairly cautious about doling out funds--except to those with a positive cash flow and a track record of success backed by solid management practices. Balancing their investors' demands to find opportunities for their pent-up capital, private equity firms are climbing back on the bull in 2011, wary of waiting too long or seeing valuations rise.

On the franchisee side, the stagnant market of the past 3 years has created a backlog of franchisees seeking to sell their business, whether to exit or to make a profit and take a second bite at the apple. These operators have spent the slow years cleaning up their act, trimming costs, shedding fat, and making operations as efficient as possible--in other words, priming their organization for a sale when the economy recovered. Their time is now, say experts. Multiples are rising, but not to the excessive levels of the boom years, making the current environment a potential win-win opportunity for both sellers and buyers.

A growing understanding on both sides of the buy-sell equation--private equity "getting it" about franchisees, and operators educating themselves about the private equity market--combined with the "perfect storm" of pent-up capital seeking investments and operators seeking capital for growth as the economy tilts upward for the first time since 2008--looks to make 2011 an exciting year in the multi-unit franchising arena. Here, in FAQ form, is what our ad hoc panel of experts have to say about the year ahead for multi-unit franchisees considering taking on a private equity partner, or simply selling out and heading for their favorite fishing hole, golf course, or new venture.

What is private equity?

Private equity is a "hodgepodge," says Harry Loyle, managing director of Cybeck Capital Partners, and it comes in all shapes and sizes. The simple definition, he says, is "private money that involves equity transactions, but under that there all kinds of opportunities."

"Private equity comes in a myriad of forms, fashions, and has different criteria important to them," says David Stiles, senior vice president at Trinity Capital, which recently served as financial advisor to multi-unit firm Breads of the World in its sale of 20 Panera Bread restaurants in Ohio to Covelli Enterprises. "There are private equity interests out there to match whatever you require." And it can take on lots of different forms, depending on the agenda of the multi-unit franchisee.

In terms of scale, most franchisee deals are small potatoes in the private equity world. From the $1 million or less that Cybeck provides (Choose Your Partner Well), it's not uncommon to see private equity deals in the hundreds of millions and well into the billions. And franchisee companies have been involved in larger deals over the years. The largest now in the news would involve Goldman Sachs's GS Capital Partners buying Apple American Group from Weston Presidio Capital for what likely will be several hundred million dollars if the deal closes. Apple American owns and operates about 270 Applebee's and reported sales of $665 million in 2010.

What are the upsides?

Private equity is a tool that can be used for many reasons: exit/succession, partial exit, strategic acquisitions, to meet a development schedule, remodeling, or as the answer to a distressed operator's prayers. For the right operator at the right time, it can bring many advantages.

"You get people who understand professional management and in many cases are finance experts who will work with your CFO to use capital efficiently," says Dennis Monroe, cofounder and chair of law firm Monroe Moxness Berg. "In many cases these are smart people, so their management input is good."

"Private equity firms generally are smart, sophisticated, knowledgeable, and tend to bring with them operating partners," says Cheryl Carner, who joined GE Capital, Franchise Finance as senior vice president, private equity originations in June 2010. "A private equity firm has better access to capital--their own, and the ability to get debt--to grow and remodel more easily than a smaller, individual investor." And, for the franchisee, she adds, "Where a private equity firm is making an investment on other people's behalf and is accountable to other investors, it sets the bar even higher."

"Efficiencies of scale with a private equity group equals access to greater resources, professional or legal advice, synergies, IT, and shared services across different businesses or restaurant companies," says Rick Ormsby, a partner at NDA Inc., an investment banking firm in Lousville focused on buying and selling restaurants for franchise companies with up to 200 units, valued from about $5 million up to $35 million.

A capital infusion brings not only money, expertise, and new beneficial relationships, but also a freedom that allows franchisees to concentrate on what they do best: growing their business. It can also add an element of professionalism, such as accounting, that might help save tax dollars, suggests Monroe.

"Too often, management gets involved in things that don't drive profitability," says Kevin Burke, managing director at Trinity Capital. "Private equity firms are generally led by very bright people who can tinker with and improve an organization's efficiency. They can take a lot of financial pressure off, and bring in a very skilled board of directors," enabling the franchisee to "intensify their focus and drive profitability."

"A private equity partnership brings a team of analysts, attorneys, real estate experts at levels beyond our capabilities, agrees Aziz Hashim, president and CEO of National Restaurant Development, which operates about 50 units, including Popeyes, Checkers/Rally's, and Subway. "They are larger firms with more talent and more people."

On the money side, he agrees that partnering with a private equity firm "brings a huge balance sheet. You have a lot of capital, can do what you like, and don't have to run around to banks," he says. "It's a huge advantage in having the financial backing, especially in today's financially challenged time."

What are the downsides?

On the other hand (and there always is one when money is involved), the price of money may be too high for independent-minded business owners. "Maintaining control is something the operators are comfortable with. They're used to being their own boss and operating with unfettered discretion," says Riley Legason, a partner at Davis Wright Tremaine, which typically represents the operators in restaurant brands that are taking on investments.

Partnering with private equity represents a "change in philosophy," says Hashim. "In that model, the management team--me--is an employee per se of the private equity company. There's something antithetical about that and the entrepreneur, where I'm the owner and make my own decisions."

Since he became a franchisee, says Hashim, "I never had to report to anyone, or do a presentation. I could have a really bad year, lose money, and that's my problem. If it's someone else's money, that's not necessarily bad," he says, but it is profoundly different from being your own master. For now, he's choosing to expand without bringing on a private equity partner.

Two other factors could also be a problem for the seller. While private equity investors are generally smart, sophisticated business people, that could turn into a problem when reasonable minds differ on strategy or tactics. "They may think they know more than they know and interfere" with a successful operation, cautions Monroe. "They want to be involved, with monthly calls, updates, and detailed financial information."

There's also a change of psychology and environment that comes with taking on a partner, especially one with the purse strings and its own set of expertise and expectations (as well as investors they must answer to about ROI). "You may be giving up economic control," says Rod Guinn, industry coverage leader for restaurants at FocalPoint Partners, which advises operators seeking to bring in fresh capital. "But if it's a really smart partner and you've done a good job in choosing them, you won't give up operating control. However, if your business starts to slip off plan by a certain amount, you'll have to sit down and account for what you're doing."

There also could be timing issues, with franchise agreements and development schedules running up against the requirements of the funders. "A private equity firm generally has a pretty set investment horizon, generally about 5 years and a couple additional to harvest investments," says Carner. "They're not going to be involved in the system for 20 years. They make money by selling companies, not keeping them."

Why now?

As noted above, the timing is right for both sellers and buyers. "I get calls all the time, looking to invest in the franchisee side," says Monroe. "Part of it is that there's so much demand, pent-up capital, and at some given point they have to deploy it."

"The market is incredibly robust, with more supply than demand, more dollars chasing loans," says Carner. This creates a favorable environment for both the borrower and the private equity firm, as well as the lenders and deal-makers. "Last year was a very active year for us following a very quiet 2008 and 2009. We saw the rebound in M&A activity and a willingness of buyers to buy and sellers to sell."

So, is it a good time to sell? "Yes, I would say so," she says, "but it depends on franchisee performance and the sector they're in."

"Private equity has a lot of money that needs to be placed. Better franchisee groups can present an attractive investment platform, if they have great management and good cash flow," says Legason. And on the sell side, he adds, "Operating groups are definitely considering private equity as a growth strategy. I think you'll find lot of larger operators are in tune with financial markets."

Historically, private equity interest in franchising has been mostly on the franchisor side (although a number of players have invested in large franchisee organizations). One reason is a lack of understanding or appreciation of the franchise model. Another is simply size: most of the multi-unit organizations a decade ago simply weren't big enough to attract investor interest. However, as investors' understanding of franchising grew, so did multiples, which made deals less attractive to investors seeking a high return on their investment.

Today's lower multiples for franchisee companies following the peak years of 2005 to 2007 are another factor driving M&A activity in 2011. "With multiples down, there really is an opportunity for upsides, because multiples will come back," says Monroe. "They're not terribly low, but they are low enough for some upward movement." When multiples got too high, private equity investors found it difficult, if not impossible, to justify investing in high-performing franchise firms.

The real key for private equity, says Monroe, is to find a good operator with real estate rights and the capacity to grow, so they can leverage their investment for a good return, and sell. Monroe notes that most of the private equity firms that invested in franchising did so in the early 2000s, so exits should be starting to appear now.

How important is the relationship?

The relationship is the most important element of private equity transaction, says Legason (see Two Critical Factors). After all, seller and investor are going to be partnered closely for years. "Is the group a good fit in terms of how the relationship will potentially play out? That piece is often very difficult to ascertain. Everything sounds good going into it." When performance is less than expected or growth is slower, especially because of unforeseen challenges, how well will the parties work together under pressure?

"The key thing is the relationship," agrees Monroe. "Do they really understand the operator? Are they patient, don't micromanage, and let you do what you do best? The franchisee has to be able to control the operating decisions. Most private equity groups agree with that." In fact, it's why they were interested in the franchisee in the first place.

"Private equity has kind of a mind of their own," says Stiles. "Their vision of what they want for the private equity company could conflict with the vision of the franchise company."

Thus it's critically important for both parties to "fully vet any opportunity, do due diligence as much as they possibly can," says Legason. "The more the parties get to know each other and understand their respective goals, the better. It's rare to see a deal go quickly."

What are your goals?

Just as private equity comes in many shapes and sizes, so do the ways it's deployed. What is the motivation of the operator? To expand through the acquisition of new units or territories? Fulfill their development schedule when banks aren't lending? Have capital available when an opportunity arises? Remodel or upgrade their units (an expensive proposition if a significant number of your restaurants or hotels are due for a facelift)? Make the first step toward the exit through a deal that requires the operator to stay on for a number of transitional years? Family succession? Or simply to sell the company and retire?

In some deals, says Stiles, operators can do partial cash-outs and stay on as they phase themselves out. "If they want to take some chips off the table in terms of a distribution, some private equity firms are okay with that." Is it time to put the kids through that Ivy League college? Finally buy that vacation home by the lake? Travel with your spouse, now that the kids have moved out? The shape of the deal really depends on the stage of your business and your goals over time.

"For the next few years in our business lifecycle, what is the trajectory? Do we want to supercharge or put it on steroids? Do we give up control, majority ownership, as the price to pay to play in the big leagues?" Hashim asks. As for whether or not to take on a private equity partner to achieve his goals, "It's a business decision for me, the emotional part is not critical to me. I have not written it off by any means. I continually review our business plan."

Are you big enough?

The answer to this depends on the size of the fund, its focus (restaurants, service, B2B), the time horizon on their capital, and, often, personalities. Opinions vary on how big a franchise company has to be for a private equity deal. Here are some thoughts from the experts.

With the cost of due diligence (time, energy, money), private equity firms often need revenues of $10 million, $20 million, or $30 million to make the deal worthwhile. "We always had some pretty large multi-unit operators out there but nobody understood it. Now they do," says Loyle.

"Franchisee deals are very small for these guys," says Hashim, and the opportunity costs of getting in bed with franchisees are a factor. "They can place $200 million deals at the drop of a hat. You have to get to a point where it makes sense for them to entertain smaller deals."

Most private equity deals on the operator side have been in the $3 million to $15 million range, says Monroe. "In most cases it's been smaller players looking to hook up with significant operators."

Private equity firms won't buy something with 5 units, they want large transactions in good brands that they can scale, sales in the $30 million to $50 million range, and/or an EBIDTA of at least $4 million to $5 million a year, says Yarkin. "Generally, they're looking for a decent-sized transaction. If they're a billion-dollar fund, they won't look at a million- or two million-dollar deal."

"There is a slowly increasing number of private equity shops that will look for multi-unit franchisees rather than the franchisor; or will look for multi-unit franchisees alongside a franchisor," says Guinn. He says investors generally set two conditions:

- Cash flow. "A few will look at multi-unit franchisees who have $5 million in annual cash flow, but more will look at $10 million and up."

- The brand(s). "Every investor I've spoken with who has looked at multi-unit franchisees has limited the concepts they would look at to the 'tier 1' national concepts, for example, a cluster of Taco Bells or Pizza Huts," he says. "The reason is pretty logical because these private equity investors never intend to own the business forever and want to be able to turn it around in four to five years after they work what they think is their magic."

What about the franchisor?

The last (or possibly first) piece of the puzzle in a private equity deal is the franchisor. Examining your franchise agreement and the FDD is essential. Obstacles to a deal might include the time horizon, personal guarantees, noncompetes, and approval of transfers.

"We counsel our clients that before even engaging with private equity, they understand what their FDD says about it," says Ormsby. For example, if a 50-unit Denny's operator is approached by a private equity firm with a fund that's in year four of seven, and the operator's FDD says any private equity has to be in for five years, no deal is possible without flexibility on the part of the franchisor.

The franchisor also might balk over the issue of personal guarantees. For example, he says, if the operator is obligated for $5 million in personal guarantees, says Ormsby, "The franchisor has to understand how that payment will be guaranteed. The operator may be obligated to guarantee it, but with a private equity firm, it's not the same."

"The franchisors are learning that dealing with a private equity investor, a substantial institutionalized investor, limited partners, and hundreds of millions of dollars, is very different from dealing with an owner-operator," says Carner. However, she says, the issue of personal guarantees is not insurmountable. "We have heard franchisors have recognized that fact, that it doesn't make sense, and see the sense of having professional investors involved in their system."

"Normally most franchisors can work through that, particularly if the operator is on the hook," agrees Monroe.

"A lot of franchisees aren't paying royalties on time now, and are struggling with hard-set remodeling dates. Some operators can't borrow the money to do it, so how do you handle it contractually?" says Ormsby. When a private equity deal can help solve that problem and keep the units operating, that's a plus for the franchisor and the brand. "Franchisors are having to learn how to accommodate private equity firms," says Ormsby.

Two Critical Factors

Riley Legason is a partner at the law firm Davis Wright Tremaine and leads the firm's national restaurant industry practice group. "Our firm typically represents the operators in restaurant brands that are taking on investments," he says. "We help them when somebody wants to invest in them and guide them through the process."

Although his focus is on restaurants, he says that for any multi-unit franchisee organization considering taking on equity partners for growth (as opposed to an exit or sale), a successful private equity deal comes down to two core issues:

- Is the investment fair in terms of the pricing? That is, is the amount of money the private equity group invests for the percentage they get reasonable, or are there better alternatives for the franchisee group? The answer to these questions, he says, varies from group to group, but the issue the franchisee group always wrestles with is: Is this the best option in terms of our growth plan.

Related issues include: What does the investment look like on the payback schedule? Are there certain preferences attached to the percentages that will make it difficult for the business operator to continue to exist as they have in the past, i.e., depending on the terms, the investor group will get a certain amount of capital paid back before the operators do. Sometimes this makes great sense, sometimes it doesn't, he says. - Is the relationship moving forward a good fit? Perhaps even a bigger--and more important--issue operators wrestle with, he says, is the relationship with the people who have invested in them. In other words, can you play well with others, or do you need to maintain your autonomy and remain in charge?

"The partner will have a vested interest in being sure their investment is put to good use," says Legason. Whether they have a majority or minority interest, equity investors are not inclined to be silent partners, he says. "They'll want membership on the board and to weigh in on important decisions. When you have someone new at the table voting on the decisions, many operators are not accustomed to that; some are comfortable and have done it before, others are not."

Life after the deal

When a business is making money, everyone is incredibly happy, says Legason. When it fails to meet expectations, "That's where things can get pretty complicated when you have a number of people with authority at the table."

As an attorney advising restaurant operators seeking private capital, Legason has been involved in deals that later turned out good, bad, and ugly. "We've seen a number of investments that have worked out very well," he says. "We've also seen the other side of the spectrum."

When it works (the good): "We've seen some very good outcomes with some clients. There's a group invested in one of our clients that has management in place that really connects with our client and their industry. They've played a very valuable role-- mentorship, strategic, and advisory."

When it doesn't (the bad): "Often clients have agreed to terms that in hindsight don't seem so fair economically. It felt like a great fit moving in, but when they get down to working together the relationships do not work out so well. The investor wants to wield more influence, there are differences in strategy--it exhausts both sides and makes the experience of being in business less enjoyable."

When it really doesn't (the ugly): Assuming the business is still viable, he says, the deal often ends with a buyout, with one party staying or both moving on. "Like in marriage, divorce is never easy, and never inexpensive. The damage has been done, and it's not always easy to recover. Sometimes another group will want to step in and take over from the investor," he says. Sometimes it's too late, so do your diligence.

Choose Your Partner Well

In July 2009, John Ikirt signed on as a ComforCare Senior Services franchisee in Dayton, Ohio. He did it with the advice and funding of a private investment company with a unique approach: investing for the long term as a 50/50 partner, rather than the typical 80/20 deal with an exit written in stone some 5 to 7 years later.

Ikirt approached Harry Loyle, managing director of Cybeck Capital Partners in Dayton. "Banks weren't really lending money unless you had collateral, and this is a service industry so Harry was an option."

Ikirt, who spent 16 years in sales management with Johnson & Johnson, saw the homecare business as a good fit after he left J&J voluntarily. "On the pharma side, there was lot of right-sizing and downsizing going on, I traveled a lot, which just got old, and I always wanted to be my own boss and business owner."

As it turned out, Ikirt already knew Loyle through networking, and was spared the time, uncertainty, and due diligence of searching for a private source of funding to start his business. "If you do seek outside help like I did, interview people so you find somebody who's a good match and who understands what you're trying to accomplish," says Ikirt. "I think it's important to interview different people. I didn't have to do that, I was very fortunate, and we were a good fit for each other."

And in terms of the operations, being a 50 percent stakeholder, says Ikirt, "I still have control." But beyond that is the relationship. "The nice thing is that it's not just I can find capital if I need it, but I have somebody who has really extensive business experience," says Ikirt. "I think it's a unique relationship. I don't know that if the bank gave me money I'd have that."

Cybeck, says Loyle, is a boutique private equity firm specializing in operating partnerships. Besides putting money into the deal, Cybeck provides management consulting, financial expertise, even coaching. "We play in a very small end of the market," he says. But with the credit crunch, "We're getting more calls than we can handle." Traditional banking relationships are not working, he says, and small businesses no longer have access to capital.

"Because I have a good relationship with Harry and Cybeck, if I need money to cover payroll, I can draw that," says Ikirt, adding that operators should at least consider private equity as a source for growth capital "in these times when banks aren't lending. I'm also not so sure if the banks were lending that I wouldn't consider an equity partner."

Use your equity wisely

Since one of the most challenging decisions an entrepreneur has in their lifetime is capital construction (what kind, what terms, when), Loyle says he has a "little speech" he gives to potential clients. "You must be sure you're expending that equity at the right point in your development. If you can accomplish your goals and aspirations without private equity, don't do it; don't spend your valuable currency and interject another person into your company."

The biggest point in any private equity transaction, says Loyle, is to "understand that equity is your most valuable currency. So do your due diligence and be sure the partner you're choosing is consistent with your values and aspirations."

In a typical private equity transaction, he says, the private equity firm picks up 80 percent and the franchisee keeps 20 percent. "Our transactions are 50/50 equity, we structure a true partnership," says Loyle. "Because of that, we spend a lot more time understanding the individual than the transaction."

For Loyle, it's all about who you are partnering with. "You have to be very comfortable that you have mutual values and culture." If you do, he says, "Twenty percent of a $100 million company is better than 100 percent of a $1 million company." Bringing in an equity partner, he says, "is not inherently bad, but it is inherently challenging." One of the most successful deals he's done took a company from $200,000 in revenue to $15 million in 5 years.

For Ikirt and Loyle, the partnership seems to be working well, with the business growing from $400,000 when he started to $600,000. And, says Ikirt, "I think it can be much more."

Ikirt says he's already thinking about expanding into other areas, and that's where Cybeck and Loyle will come in again. "Even if it's a franchise or some kind of startup business you're getting into, there's a lot of trial and error. With Harry, he's been there before. It takes some of the pain out of some of the growth we've gone through, and he also paints a picture of where you're going in the future," says Ikirt. "I have an MBA, but there's nothing like having a partner who's living in the real world."

Share this Feature

Recommended Reading:

STAY CONNECTED

Subscribe to our newsletters to stay informed on the hottest trends in Franchising.

FRANCHISE TOPICS

- Multi-Unit Franchising

- Get Started in Franchising

- Franchise Growth

- Franchise Operations

- Open New Units

- Franchise Leadership

- Franchise Marketing

- Technology

- Franchise Law

- Franchise Awards

- Franchise Rankings

- Franchise Trends

- Franchise Development

- Featured Franchise Stories

FEATURED IN

Multi-Unit Franchisee Magazine: Issue 2, 2011

$200,000

$225,000

The multi-unit franchise opportunities listed above are not related to or endorsed by Multi-Unit Franchisee or Franchise Update Media Group. We are not engaged in, supporting, or endorsing any specific franchise, business opportunity, company or individual. No statement in this site is to be construed as a recommendation. We encourage prospective franchise buyers to perform extensive due diligence when considering a franchise opportunity.

The multi-unit franchise opportunities listed above are not related to or endorsed by Multi-Unit Franchisee or Franchise Update Media Group. We are not engaged in, supporting, or endorsing any specific franchise, business opportunity, company or individual. No statement in this site is to be construed as a recommendation. We encourage prospective franchise buyers to perform extensive due diligence when considering a franchise opportunity.